Saturday, December 23, 2006

How much should you pay?

A Note on the profit based valuation process of ABC

"The basic objective of the valuation was to determine what we can pay for a company that can generate about 25% return on equity.

In trying to determine a multiple of profits we can pay for such a company, we would need to find out the organic (meaning, without additional infusion of capital) growth potential that it has. The metric to determine this growth is a function of current ROE and percentage of the retained current earnings. To explain this concept, intuitively, a company with a zero ROE would have no growth since it is not generating any capital for redeployment in the business and would work with same capital as it had in the beginning of a given period. Either the ROE has to turn positive or there has to be additional capital infusion for it to have any growth. For a company generating positive return on capital, the organic growth would, hence be a product of the capital it retains and the ROE. This is the first of the bases of valuation.

Arguably, either of these variables can change – ROE due to change in product profitability or similar and capital due to additional infusion/withdrawal. However, this is a decision down the line that we (as a controlling stakeholder) will make and hence, should not pay the current owners of ABC for. Hence, this metric of organic growth has no subjectivity involved."

Continuing on the above part of my note:-

ROE is the net profit available to shareholders divided by Shareholder's Equity (Book Value). This can be easily found by dividing EPS by Book Value Per Share.

Friday, November 17, 2006

Divergent Paths - 3

Coincidentally, I started buying Glaxo also on the same day. Glaxo was also a de-regulation play, in a sense. Most of the medical drugs in India at the time were under the Drug Price Control Order (DPCO), whereby the government controlled the prices at which drug companies could sell their products to consumers. As a result, the profits were depressed artificially. I looked at Glaxo and there was not much in the form of book value for my downside protection. It was around 66 and the share was trading around 400 at the time. The book value did not include the value of drug patents available in the quiver of its parent, which held controlling interest in the Indian company. The company had grown its book value @ 6% per year for the last 8 years and had an ROE of 13% pre-merger.

Glaxo came to my attention for one reason. I used to buy diabetes medicine for my grandmother on a regular basis. She swore by a pill called Diaonil prescribed to her by her doctor. If this was the case for a 70-odd year old lady with only basic education, I wondered about the rest. I found out that Glaxo marketed this drug. Later, talking to a friend who was a medical representative, I got a good understanding of the business model of the drug companies operating in India.

There were some other metrics that pointed to the direction the company was taking. There was also the proposed merger with Smith-Kline Beecham during the year. And a quick growth was in sight. I admit, there was nothing much in the balance sheet pointing towards a great share. Despite that I ended up buying it at an average cost of around 318 till Jan 03. By the end of 2003, I had a two-bagger in my hand and by March 06, it was at 1450. I had sold part of my holdings by the end of 2004 to retrieve capital. Looking at values till March 06, I had an IRR of 43.74% and an NPV of 23,143 on an investment much less than that.

Divergent Paths - 2

BPCL was a de-regulation play. The government had dismantled the APM mechanism through which subsidies were distributed to oil companies to keep the petroleum product prices down. I had friends who audited one of the local refineries and had heard war stories about the mechanism. Now, the companies were free to set their own prices; or so, it seemed.

Based on the 2000 financials, the book value of BPCL was at Rs.232.98 per share. However, that was of not much use to me since they had done a 1:1 bonus issue (stock dividend) during the year. By a reasonable estimate, the book value would have been around 130 considering the growth during the year. However, the enterprise value (EV) of the company seemed to be around 250 per share, which was what I was hoping, would come to my rescue. The relevance of EV is that BPCL would not have had to face competition from other MNC oil companies when they entered, since it would have been easier for them to buy BPCL at 233 or less per share and use the control to capture the Indian market. If they decided to build a new refinery and establish the same infrastructure that BPCL already had, it would take time as well as more money to compete. Inflation was working for me for a change. The other factor was the EV/PBIDT ratio looked pretty good at 3.4 times for 2000, which means that a deep pocket buyer could buy all of the shares of BPCL from the market and pay down all of the debt in the balance sheet and come-up with about 20% return on the total equity. (20% is approximated by inverting 3.4 and adding for tax protection of debt, since interest is tax deductible and profits are not).

Initially the new system of market pricing seemed to work. In FY 2003, BPCL posted a decent year with a 47% growth in EPS. Return on Total Assets (ROTA) went up by 42% that year from around 11% to 15%. Operating efficiency seemed to have caused the growth in EPS.

There are two components of efficiency for most manufacturing companies – operating and production efficiency. The Operating efficiency is measurable as a ration of EBIT to Value Add (Value add is calculated by deducting the material cost from sales. As the term implies, this represents the value added by the operations of the company). For oil companies, this component is called marketing margins, since this represents a higher price realization for them. This is the component of the price charged for making the by-products of crude available at the pump. There is also the component of Production efficiency (called Refining Margins for oil companies) which can be calculated as the ratio of Value Add to Sales. This is the component of the price charged for converting the raw crude to its various by-products.

BPCL seemed to have improved its marketing margins that year to compensate for a slight decrease in the refining margins. However, something that puzzled me was the increase in the inventory turnover. It had gone down by about 19% from 14 to 11.

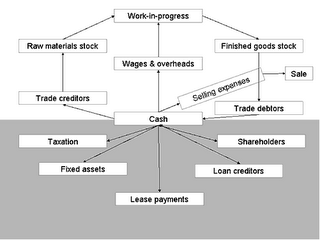

For a manufacturing-cum-retail operation, there are two key factors/cycles that determine its ability to generate cash. One is the manufacturing cycle, which is a function of the throughput time, wherein raw material is converted to finished product. Second, shared with any product/sales operation, is the working capital cycle wherein cash is used to buy materials which are sold to customers to become receivables and later converted back to cash. These two critical cycles determine the cash generating ability of any operation.

As an aside, the beauty of the software companies that work on a turn-key or T&M basis is that they don’t have the first cycle and they have a short second cycle with a higher margin.

The efficiency of the cash generation is dependant on two factors – one is the margin in the cycle and second is the speed of the cycle. When I was a kid, I remember seeing the manually pedaled irrigation wheel looking something like this .

It would have a big wheel with buckets at even intervals. It worked like a smaller version of the ferris wheel. It was pedal operated or animal operated and the buckets would fetch water from a lower level to the fields. I saw these two cycles the same way. The margins represent the depth of the buckets. A smart farmer could figure out that the quantity of water he would irrigate would depend on the size of the bucket and the speed of the wheel. The cycles in the product business are similar – the faster turn and higher margins assure more cash generation.

It would have a big wheel with buckets at even intervals. It worked like a smaller version of the ferris wheel. It was pedal operated or animal operated and the buckets would fetch water from a lower level to the fields. I saw these two cycles the same way. The margins represent the depth of the buckets. A smart farmer could figure out that the quantity of water he would irrigate would depend on the size of the bucket and the speed of the wheel. The cycles in the product business are similar – the faster turn and higher margins assure more cash generation.For BPCL, the buckets had deepened. However, the pace of rotation had gone slower in one area. The pace is measured by the asset turnover ratio which is Turnover divided by total assets. This can be further broken down into: Fixed Asset Turnover, Inventory Turnover, Receivables Turnover and Cash Turnover ratios. These are ratios of sales to fixed assets, inventory, receivables and cash respectively. The component turnover ratios are a way of looking at the pace at different stages of the cycle. For BPCL, there was a slow-down in the inventory side (which meant that inventory was higher in relation to sales) and a growth in the receivables side (meant faster collection). The higher receivables turnover more than offset the slow-down due to inventory accumulation. The asset turnover was higher by 19%. This is typical when you have a year of high growth.

Another way of looking at these is the number of days the working capital cycle takes. It can be approximated by converting these component ratios into number of days by dividing 365 by these ratios. In BPCL’s case, it had actually declined from net 32 days to 39 days. The 7 days seemed to be on the inventory side. However, this was no cause for much concern.

The party did not last as long as I expected. The pooper turned out to be crude oil prices. The trouble with dealing in a commodity like petroleum products is that its demand is inelastic. In layman’s terms, it means that people don’t buy less of petrol (gasoline), diesel etc., just because the prices went up by a few cents; at least over a short-term. Over a longer period of time, the car companies may market more fuel-efficient cars aggressively and technological innovations like the hybrid/electric cars may pop-up. But it takes a long time for all these to happen. And, when this happens, the beneficiary definitely wouldn’t be a non-integrated refiner who buys crude from another business and sells at soft-regulated prices.

I started buying BPCL in April 01 and kept on buying all the way till 2002. My average price was around Rs.200 per share, which gave me a good margin of safety from the EV of around Rs.250 or more. For some time, my thesis seemed to have worked out pretty well. The shares traded at a high of 520 by Jan and remained thereabouts till April 04. After that, the bottom seemed to drop out and the shares went all the way to 330 levels and seemed to stage a small rally through Jan 05 and back down again at 360 levels by the end of April 05. I sold some of the shares by the end of November 04 at around 394. It started another climb from the 340 levels and I sold most of the rest around 365. By the time I exited most of the position in Aug. ’05, I had made an IRR of 21% including dividends with an NPV of 4614 at the 12% required rate. Phew!!! What a roller-coaster ride.

Divergent Paths - 1

Saturday, October 28, 2006

Options Seminars

1. The Delta Risk - The risk of share price movements affecting options prices

2. The Vega Risk - The rapidity of price change of share prices causing the options price to change

3. The Theta Risk - The time factor which is basically the interest cost.

I stuck to pure stock buying for the simple reason that it had only the Delta Risk. Vega risk wasn't measured or was smoothened away. The theta risk was absent since I used only own money and no borrowed money. (It could be argued that there is an implied cost to own money - the opportunity cost and that Theta risk is not entirely absent.)

Steve Meizinger of OIC did a great job of laying out the advantages of a spread. I was surprised to learn that spreads could be used to take exposure to the right kind of risk and hence be rewarded for taking the right position. For instance, you could build a position on INFY by buying a 45 call and selling a 55 call for the same expiration. This would mean that the move from $45 and up less the options premium paid would be the profit. Using options means that the capital outlay would be much lower and the returns higher per $ capital invested.

The flip side is that the whole capital could be lost. However, since it is a spread we are discussing the loss is also limited to the net options premium paid.

In this example outlined, the volatility risk and theta risk between 45 and 55 call would almost even out to zero. The only risk exposed would be the Delta risk, which is what you are trying to make use of when you invest in a share.

It gets a little complicated when you buy a LEAP and start writing options against it. It is almost similar to buying a stock and writing calls against it. The risks are much higher in the former case; so are the returns.

I'll post on my ventures into this field.

Sunday, September 24, 2006

The Poker Face of Wall Street - Review

I had an opportunity to read “The Poker Face of Wall Street” by Aaron Brown. After reading, I still couldn’t figure out whether it was a case of the man with the hammer seeing nails everywhere or not. However, there are some good insights into risk, chance and life, in general in the book. A few that I liked follow:-

Risk Rules:-

- Do your homework – You must avoid unnecessary risks and, just as important, avoid taking risks blindly when they can be calculated….you must take risks only when you’re getting paid enough to do it.

- Strike for Success – risk taking requires “Prudence and Courage; Prudence in contemplation, Courage in execution.” If you decide to act, act quickly and decisively. Go for maximum success, not minimum risk….”From this moment, the very firstlings of my heart shall be the firstlings of my hand.” – quoting Macbeth

- Make the tough fold – “Your first loss is your least loss”….If the result of that calculation suggests that you are not getting sufficient odds to justify further investment, give up just as quickly and decisively as you began.

- Plan B is You. The only assets you can count on after a loss are the ones inside You: your character, your talents and your will.

Quoting David Sklansky’s famous Fundamental Theorem of Poker:

"Every time you play a hand differently from the way you would have played it if you could see all your opponents’ card, they gain; and everytime you play your hand the same way you would have played it if you could see all their cards, they lose. Conversely, everytime opponents play their hands differently from the way they would have if they could see all your cards, you gain; and everytime they play their hands the same way they would have played if they could see all your cards, you lose."

A Brief History of Risk Denial:

- All our financial products are pure, with no artificial risk added

- It’s capital formation, not gambling

- Traders are order clerks

- It’s not gambling; it’s hedging

- Insurance payouts go for sensible investments, while lottery winners waste their payout.

- We’re not gambling, we are investing

- The ups and downs of the stock market just reflect the ups and downs of the economy

- Governments set interest and foreign exchange rates

- Derivatives aren’t gambles

Scanning for Options trading opportunities – quick tips:-

Parity – Look for a situation where strike price plus call price minus put price is significantly different from the price of the underlying

Verticals – Buying a call or put, and selling the same kind of option on the same underlying with the same expiry, but at a different strike. When a stock is selling at the midpoint of a vertical, the vertical has to be worth very close to half the spread.

Calendar – buying one option and selling another of the same type, with the same underlying and strike but a different expiry. Longer dated options are more valuable than shorter dated ones. The spread is most valuable near the current stock price and should decline in price for options at higher and lower strikes.

“Everyone is an opponent-not a vindictive opponent; just a decision-making entity maximizing its own utility function without regard for your welfare.”

“The ultimate scarce resource in cognitive processing is attention. Things are going on right now that we’re not paying attention to. Information is flowing all around us, ignored. The trade-off is between attention and memory. A court stenographer can record every word everyone says in court, while reading a novel, but ask her what happened ten seconds ago and you get a blank stare. Attention is the tool you need to get information. People are using unconscious strategies because they don’t have the attention to solve everything optimally. We can predict their actions using simple game models because they’re not paying attention, not because they are.” quoting Colin Camerer

Saturday, September 23, 2006

Cost Inflation Index grows five-fold in 25 years??

This headline recently caught my eye - "Cost Inflation Index grows five-fold in 25 years" ?? The author is someone I respect for his good writing in Business Line. I have enjoyed his articles while I was a CA Student in the late 90s. I still do respect the quality of his writing. However, the tilt of this particular article made me wonder.

I wanted to put it in perspective. A back of the envelope calculation would show that a 5-fold increase in anything in 25 years is less than 8% per annum (the spreadsheet would show 6.81%). 8% is close to the interest rate prevailing interest rates for India during this time period.

"In the first few years, CII grew only by single digits. The latest jump is of 22 points, from 497 in 2005-06. The biggest increase thus far was in 1999-2000, when CII vaulted by 38 points to reach 389."

These lines again made me wonder. Of course, the single digit growth in the initial years is a property of any price index. Since the base is low - 100 in 1981-82, as the article points out - the year-on-year (YOY) growth would be low too. That is a 9% inflation in 1982-83 would make the 1982-83 CII to 109. However, as the index grows in value to say 497, the growth would also be magnified. The 22 point jump amounts to only a 4.4% rate compared to the 9% in 1982-83. This should be good news, really, going just by this jump!!!! The 38 point increase in 1999-2000 is a 10.8% increase, not so good news. But compared to the 1982-83 inflation, it is only a 1.8% higher rate. It also would suit the prevailing conditions in the economy - the after-effects of the IT boom and all.

My interest in bringing all these numbers up is to prove just one point - it is the relative values that matter, not absolute. I have seen the same thing happen with the reporting of Sensex values as well. A 200 point rise in a day when the index is at 11000 is only less than 2% and is equal to an 80 point rise when index was at 4000.

Tuesday, August 22, 2006

The Plunge - 3

Godrej Soaps Ltd was a spin-off value play. It owned various popular brands, in addition to a contract manufacturing (CM) operation using their plant’s surplus capacity. Typically, the FMCG (Fast Moving Consumer Good) soap and cosmetic line of business is a lucrative one if the brand building has already been done. It was so in Godrej’s case (Godrej da jawaab nahin was a slogan I remembered from my early school days). Their marketing machinery was pretty good, worthy of giving a run for the money for the MNC brands. Cosmetic marketing is basically a combination of peer pressure and a scare tactic. It usually plays on the fear of being left out, whether it be Listerine initially in US on halitosis or Fair & Lovely cream with its play on not being fair being a marriage breaker.

However, the problem with Godrej was that it was hard to delineate the profitability of the FMCG business with the CM operation. CM operations tend to usually suck cash due to huge inventory needed. This is not true for FMCG business, where the cost of the inventory tends to be lower in relation to sales (the good ones have negative working capital). It is for a similar reason that conglomerates command a lower P/E than focused companies. The good thing with GSL was that the management was aware of this and decided on the spin-off. This made GSL a typical event play.

The spin-off of GSL into Godrej Industries Ltd (GIL) and Godrej Consumer Products Ltd (GCPL) happened and the release in value was almost immediate. I bought the whole entity at Rs.55. When GCPL listed, it started quoting at Rs.58 in Oct, 2001. The price at which GIL was quoting was all profit for me. However, attracted to the value of the intangibles, I was buying demerged GCPL in 2001. I ended up selling GIL for Rs.16 in Apr 02 and most of GCPL around 150 in Oct 03 attempting to release my capital.

I have tried to evaluate these two batches of GCPL differently. One being the spin-off play for my GSL purchases and the other a regular value play for GCPL stand-alone purchases. It turns out that the Spin-off play (GCPL, GIL collectively) returned me an IRR of 75% (monthly 4.8%) in a time period of less than 3 years. Excess return measured by NPV was at Rs.2,277 against my initial cost of 1,379 and future date NPV till 2004 was 3,199 at 12%. I sold the rest of GCPL(stand alone) in Feb 04 at around 182. It returned me 81.79% in 3 years with 5.11% monthly and NPV of 4,410.

However, I was in for another surprise with GCPL. I did not seem to have valued GCPL correctly when I sold it. In the 11 months, it went all the way up to 276. I have again and again sold early as my later evaluations will illustrate. It is very difficult for me to predict where value discovery process by the market stops and speculative activity begins. Hence, I take the best course of action that protects capital. I re-deploy it into other investments with better chances of success. In GCPL’s case I decided to buy again in Jan 05 at 277 and the returns till date have been stellar. An IRR of 123% in 15 months at a monthly rate of close to 7%. An NPV of 7,306!!!! However, this story has not ended yet.

The funny thing is I don’t seem to have evaluated the financials of GCPL. I need to do that to make sure I do not need to act soon at least to release my capital at current prices. The FMCG play in India seems pretty straight forward so far. The IT industry brought higher disposable income in the hands of the educated middle class. This is one of the aspects of growth in the services industry in a heavily populated country. A manufacturing led growth does not necessarily lead to growth in PDI. The value add (Price less material cost) for services is very high, especially so for IT industry. ( I am reminded of the infinite wisdom of the KGST who decided to tax the software CDs at their sale price. Either they had no concept of IP and intangibles or they didn’t care to make the difference).

The Plunge - 2

Reliance was almost a no-brainer. This company never posted a degrowth in turnover for the past few years. The EPS for FYE 2000 was Rs.22.82 which meant that I was getting one of the leading companies in India at around 13 P/E. However, my basis for buying was based on the assumption that the EPS of RIL will grow at 25% going forward and I would be able to sell it at the same P/E some years forward. 25% seemed realistic looking at the growth from 1999 to 2000. In retrospect, I made two errors due to plain ignorance.

- I assumed that the P/E ratio was reasonable considering the then prevailing interest rate environment.

- I assumed that growth would follow a linear trend.

Over the period of 4 years following, I seem to have gotten back my entire capital back through some sales (it is a strategy I follow) and still hold the same value of RIL. As on 3/31/06, it roughly translates to an annualised return of 34.5% at a monthly rate of 2.5%.

Measuring Performance

The returns I will be using here are monthly rupee weighted returns linked geometrically to produce the annual return. There are two prominent and valid methods of measuring return. One is to measure the growth of a unit of currency over a period of time and the other is to measure the return weighted for the transactions for each period. The first measure is more appropriate when calculating returns for something where the entity being measured does not have control over the cashflows. Money-weighted returns (basic as an IRR) is more appropriate where the entity measured has control over cashflows. Clearly, this method is appropriate for my purposes, since I am in charge of sale/purchase decisions and investment of cashflows.

IRR has an inherent flaw in that it assumes the cashflows are invested at the same rate throughout the period of investment. However, that may not be necessarily the case here. I may have reinvested the money in other investments which may have yielded more or less than RIL. However, the difference in measurement will vary dependant on the scale of the investment in relation to the total portfolio, the range difference in returns between the various investments in the portfolio and their interaction.

Another method, I used to measure the returns was NPV. Net Present Value is the incremental value after investing at your required return. So an NPV of 0 means that your investment returned exactly the same as your required return. Anything more would be the incremental return discounted to the initial period of investment at the required rate of return. Now, we run into the question as to what is the appropriate rate of required return.

If you follow the economist’s line of thinking that capital is scarce with alternative uses, the cost of capital is the return on next best available investment; the alternative for Indian stocks may be Indian fixed income instruments. I have looked at returns of 364-day T-bill rates. However, I am following the well researched view that Indian G-Secs are not priced appropriately to adjust for inflation appropriately due to a demand imbalance from PSU Banks. The alternative investment I could find was small savings. These are comparable, especially since the time-frame of the investment under review and the SS is almost the same. NSCs would be an appropriate instrument. Adjusting for the tax effects of taxability, deductibility and rebatability under tax laws; I am going to use an approximate rate of 12% as required return.

Back to RIL

Looking at RIL, I find that my NPV is 22,641 at 12%. This is the excess return discounted back to April 2001. The value as of April 2006 will be 39,902 (that is 22,641 invested at 12% for 5 years). Considering that my investment outgo has only been 40,618, this is a very good excess return.

Measuring Performance in Dollars

A side note – The US dollar return for all the investments under evaluation would be more than the stock’s return by around 1.4% per year and for 5 years ending 03/31/06 would be around 7% (from INR 47.69 to 44.60). This means that to calculate the US Dollar return (%) –

[(1 + S) (1 + E)] -1

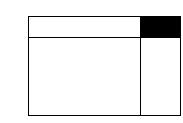

where S is the Stock Return in % and E is the exchange rate gain/loss in %

At first sight, it may seem that the US Dollar return would be as easy as adding up the US Dollar gain/loss and the stock return. However, the correct way to look at it is in terms of area of a rectangle, where the S & E are the increase in the sides of the rectangle. If the length (assume S) increases with breadth remaining constant, the area would increase proportionate to the increase in length. The same is also true for an increase in breadth. However, when both S & E change, there is a corner rectangle formed by the interaction of the two as illustrated in the following diagram. In additive method of calculating US Dollar return, this smaller rectangle formed by the interaction is left out. This corner rectangle is the result of the stock gain increasing due to increase in currency return as well.

In RIL’s case, US Dollar return would be 36.37% [(1 + .345) (1 + .014)-1]

So much for history of RIL, the question now to be considered is will RIL continue to deliver similar stellar performance in the next 5 years?

The Plunge - 1

Reliance Industries Ltd (http://www.ril.com/) - 10 shares at Rs.300 – Rs.3,007.50

Godrej Soaps Ltd – 25 shares at Rs.55 – Rs.1,378.50.

Sunday, August 20, 2006

Testing the Waters

My initial experience in buying stocks in the secondary markets had been a disaster. Circa 1996 (I wasn’t even 20 then), I audited a stockbroker for my employer and established a business relationship with them. I scoured through ET stock pages and bought two stocks. My criterion was that they were trading near their 52-week lows. (Behavioral Finance calls it Reference Point behavior). Of course, I didn’t bother to check if there was any valid reason for such a price behavior. Here are the purchase prices:-

GR Magnets Ltd – 100 shares at Rs.8.72 per share

Goodearth Organics Ltd – 100 shares at Rs.1.00 (approximately) per share

I don’t exactly recall the price I paid for Goodearth. I just know that I paid less than a 1000 to the broker in settlement.

When I placed the order, the lady at the broker’s asks me – did I know that GR Magnets’ Managing Director was arrested for FERA violations (foreign exchange laws)? Of course, I had no idea. But, I nodded along.

Electronic trading and demat were unheard of these days. The broker delivered to me a share certificate with attached transfer deed, where the seller had signed his name and with a few other prior parties’ signatures. I had no idea of the timing of the sale. So, when asked I said I wanted it transferred to my name. (It didn’t occur to me to ask for alternatives – I could have held on to the transfer deed and get it revalidated after three months, if I didn’t sell it by then. Three months, I think, was the time limit to hold the deed without sending it to the company). So I filled out the forms and send it on its merry way to the companies to get the shares transferred.

Here’s the rest of the story:-

GR Magnets – bounced up to Rs.20 within 2-3 months. Good call, I thought. However, there was one hitch. I didn’t have the shares with me to sell it. It was with the company to be transferred. By the time I got the shares back, the scrip was moved to the Z list (equivalent of having the bad boys of the class sit in the backbenches) and was trading way below my purchase price. The last quoted price was close to Rs.1. I still have this certificate and am thinking of framing it as a not-so gentle reminder of my follies of indiscretion.

Goodearth Organics – never saw a bounce, never saw the certificate again.

It was a great practical lesson in bad deliveries for me. I stayed away from the markets for the next five years, until demat came into existence.

Thursday, July 20, 2006

Freakonomics

A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything

Steven D. Levitt &

Stephen J. Dubner

(Try their blog at http://www.freakonomics.com/blog/)

It was an interesting read – it is not at all an economics book, in a traditional sense.

Here are a few pointers from the introduction:-

“Morality, it could be argued, represents the way that people would like the world to work – whereas economics represents how it actually does work…..This book, then, has been written from a very specific worldview, based on a few fundamental ideas:

Incentives are the cornerstone of modern life…

The conventional wisdom is often wrong…

Dramatic effects have often distant, even subtle, causes…

“Experts” – from criminologists to real-estate agents-use their informational advantage to serve their own agenda….

Knowing what to measure and how to measure it makes a complicated world much less so.”

“Economics is, at root, the study of incentives: how people get what they want, or need, especially when other people want or need the same thing. Economists love incentives. They love to dream them up and enact them, study them and tinker with them. The typical economist believes the world has not yet invented a problem that he cannot fix if given a free hand to design the proper incentive scheme. His solution may not always be pretty – it may involve coercion or exorbitant penalties or the violation of civil liberties – but the original problem, rest assured, will be fixed. An incentive is a bullet, a lever, a key: an often tiny object with astonishing power to change a situation.”

“The basic reality is that risks that scare people and the risks that kill people are very different…… Risk = Hazard + Outrage…When hazard is high and outrage is low, people underreact, And when hazard is low and outrage is high, they overreact” – quoting Peter Sandman, a risk communication consultant from Princeton, NJ.

Sunday, June 04, 2006

CFA Level 3 Exam

I plan to continue regular blogging starting the next month.

Saturday, May 13, 2006

Berkshire Hathaway Meeting 2006

Personally, it was a pleasure to be at the meeting. I have never spent a whole day listening to someone talk without getting bored, is to say the least. The icing on the cake was the opportunity for international shareholders to meet Warren, Charlie and Bill Gates (who is also a director). It was definitely the event of my lifetime.

Saturday, January 07, 2006

Performance of Indian Portfolio

The monthly returns are rupee-weighted linked geometrically i.e. monthly compounded. The

Total return is the best way to measure portfolio performance. The Capital gain is displayed for fair comparison since Sensex values (inserted later) and Nifty returns (inserted later)are not inclusive of dividends.

Modified July 21, 2007